On New Jazz Order, and just starting out

This week, after ten years of leading a 16-piece big band called New Jazz Order, bandleader (and one of my closest friends) Clint Ashlock took to Facebook to announce that the group would at least temporarily cease playing on a weekly basis.

Starting in 2006 or 2007, NJO had taken up residency at Harling's Upstairs, an endearingly (sometimes disgustingly) rustic bar on Main Street in Midtown Kansas City, performing every Tuesday night from 9 PM to midnight. Of course, the gig didn't really pay in anything other than free booze (and even that was kind of under the table), and the vibe was so...um...casual*, that it almost never started or ended quite on time. It became a running joke when plugging our shows on Facebook to say something like "Tonight, from 9:07 to 12:16, it's NJO at Harling's!" When someone noticed that, despite the lack of Harling's signage, the complex in which it resided was evidently called the Southwell Building, we took to calling it just "The Southwell", like a five star hotel or something.

*When I say casual, I mean that the bar had been voted "Worst Restrooms in the City" by The Pitch several years running, there were constantly leaks in the ceiling, there was no air conditioning, there was no signage on the door, taking the back entrance was prefaced by summiting two stories of wooden stairs that were so so so far below building code that I can't fully describe it; there was an inexplicably vacant room adjacent to the bar area that was filled with empty cardboard boxes, assorted furniture, empty liquor bottles from who-knows-when, it was cash-only and the "top shelf" liquor was McCormick's. A friend asked for wine once, and it was served in one of those clear plastic cups you get at the office water cooler. This place was and is surreal in all the wrong ways. We loved it.

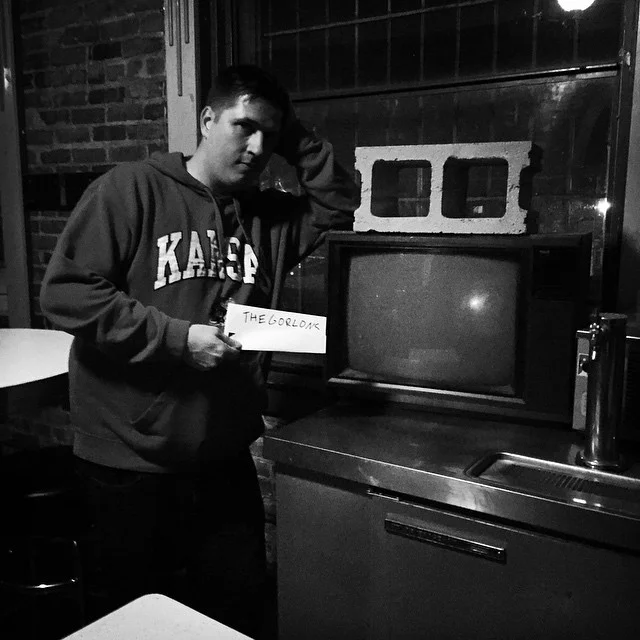

Seriously - leaks everywhere.

NJO was, really, an incredibly ambitious undertaking for Clint. I don't think I knew that at the beginning. And I also just viewed him as sort of older and more experienced than he actually was at the time. It seemed totally normal to me - of course, this veteran jazz musician would have a band! It was only today, when Clint posted some vintage photos on Facebook, that I realized he was 26 when this thing started. Twenty-six! Just a puppy, and still in school at UMKC. He hustled a weekly performance space, assembled a book that was a hundred charts deep, wrote his own music for the group, and took on the task of getting 16 people to agree to play each week, managing egos and dealing with last-minute cancellations every Tuesday. This went on for ten years. Ten. Years. And Clint lost money on NJO - the economics of a big band are such that, when the pot of money is divided up 16 ways as opposed to most gigs which usually involve 2-6 musicians, Clint's share of the money was maybe only enough to cover the cost of the checks. If there was any money leftover, it usually went to the bartender. This thing was purely a labor of love - an unmitigated act of passion for music, and for the jazz community in KC at large.

All of the items in this photo were just hanging out in the back room, for reasons unbeknownst to anybody. Except for Heinlein's KU hoodie, which he got at Kohl's.

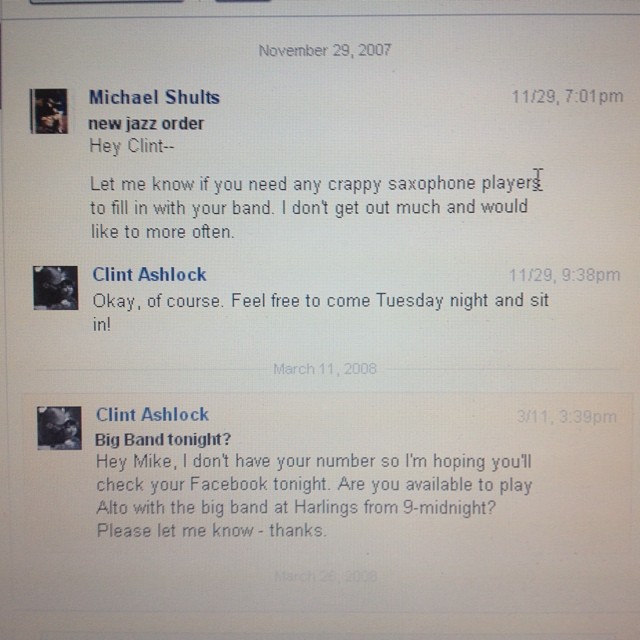

My own introduction to New Jazz Order came at a pretty pivotal point in my musical and personal life. I had been studying at UMKC for a few years, and really working hard and improving, but the process of getting out into the Kansas City jazz community and actually listening, hanging, and eventually working to get gigs hadn't really started yet. I had pretty crippling self-doubt and never felt like I was quite "ready" to go to jam sessions or try and sit in on more established musicians' gigs. Further, I had struggled socially in my early years in college - as a pretty tenacious practicer I often missed out on a lot of typical college experiences and only had two or three people I would regularly hang out with. Thankfully I had peers like Hermon Mehari, Steve Lambert, Ben Leifer, and others who would invite me out, anyway. These guys were constantly looking for a place to play, always trying to take what they were working on in the practice room out into the wild. I saw how much they were growing as a result, and I finally had to start thinking about confronting my fears. When I got wind that Clint Ashlock had started a big band, that seemed like a "safer" or more comfortable way for me to finally break out of the confines of the practice rooms and actually dip my toe in the waters. I might not have been able to hang with the best players in town for four choruses of Donna Lee, I reasoned, but I could sit in a big band section and probably play something serviceable for a chorus of F blues. So I sent Clint (who I barely knew at the time) a message:

So much hilarious about this exchange: Clint calling me "Mike", "hoping" I would check my Facebook (this was when people used Facebook on computers...), and my needless self-deprecation to try and hide how much I actually really did loathe my own playing at the time..

The learning curve was so steep, and the on-the-job training started pretty much right away: thinking I might impress some of the older guys in the band that first night, I decided to take advantage of the set break by going off in the corner room and practicing something I was working on. I had read that John Coltrane used to do that. After about two minutes of this, Zack Albetta yelled (or maybe he wasn't yelling, actually - Zack just has a very resonant way of speaking) "It's the set break. TAKE A BREAK!"

So there was lesson #1: don't practice on the set break. Put your horn away and go work the room. Thanks, Zack.

New Jazz Order was really the perfect bridge from being a student to being a professional musician. While the demographic of the band was mostly young, there were seasoned pros sprinkled throughout the band. I sat in the section with people like Rich Wheeler and Kerry Strayer in the early years. Mark Lowrey, Kevin Cerovich, John Brewer, Doug Reneau and Sam Wisman would play. In other cities, the young jazz musicians who are thirsty for playing opportunities but not getting called for gigs yet will often resort to undercutting - that is, playing for free or less than the "going rate" just to have an audience. This epidemic can destroy a scene in a hurry. This never was quite the same problem in Kansas City, and I think that's largely because of NJO and Harling's. We had our place to play.

NJO was always raw. That's not always a compliment - the intonation wasn't always pure, we goofed up the form of Clint's arrangement of Time Will Tell a thousand times, and I pretty much just played about every fourth note of the saxophone soli on Cherokee. But when I say raw, I also mean that the music was almost always real and honest and from the heart. The percentage of the output of that band that was totally sincere was higher than any musical outfit I have ever been a part of. It's not even close. And when it was on - when the right people were playing, when it was the middle of June and the windows were open and the music was pouring out onto a busy Main Street below, when the crowd was shoulder-to-shoulder, and Clint was back there throwing his patented 109 MPH fastball on Groove Merchant - man, it was SO on. Sometimes Bobby Watson showed up to play, and it was... well, you just had to be there.

"Why is there a couch in front of the band...and where did it come from?"

"Don't ask questions."

Often, especially after the group had been around for a few years and many of the members were working more and more, someone would come up and apologize to Clint. "Hey, man, I hate to do this, but I got this regular gig at..." and that would be it for them, for awhile. But there would almost always be a Next Man Up. Someone else that had been coming up to listen or sit in, waiting for their chance to get on the carousel. In other cases, musicians would move to Kansas City from other scenes. Ryan Heinlein, John Kizilarmut, Karl McComas-Reichl, Peter Schlamb, Brett Jackson ... some of the pillars of the community that didn't grow up musically in Kansas City helped get connected at least a little bit from playing in New Jazz Order, even if just for a few weeks. When calls started coming in a little bit more for me, it had to be a really good one to skip New Jazz Order. I know that I turned down at least a few hundred dollars in gigs a year to play in the band, and I'm not the only one. There were those that had been around and understood that what NJO had been and had meant to the much-ballyhooed renaissance of jazz in Kansas City over the past decade-plus, and that there was nothing analogous anywhere else in the world, and that meant more to us than a few gigs. Clint's at the top of the list. Did I mention how much money he lost keeping this thing afloat? It's a lot.

The band had many many triumphs. Clint was on the cover of The Pitch and I had this needlessly fluorescent picture run in a story about us in The Star:

We put out a CD that I'm both proud and ashamed of. Last fall, we even got invited to play at Game 1 of the World Series, which led to Clint and I meeting SPORTSWRITER JOE POSNANSKI!!!!:

At the end, New Jazz Order was even playing regularly for money that was actually pretty good, thanks to John Scott and the Green Lady Lounge.

At a certain point, the pipeline dried up, and the burden of trying to scrounge up a band every week got to be too much for Clint, with a family and so many other equally important (and better paying, usually) things on his plate. When I say the pipeline dried up, I don't mean to suggest that there is a dearth of talent coming up the ranks in KC; far from it. But more and more excuses for not playing kept coming - a paper to write, an illness, a long commute, fatigue. I'm not completely sure what to attribute that to, and that's probably another blog post. Maybe the 20-year-olds found another place to play that I'm not aware of, or maybe they have found other ways to start working towards having an actual career in music in Kansas City. Maybe. A more likely story is that they see the successes of people like Clint, Steve, Hermon, Ben, and Brett (and the list goes on) and don't understand all of the less-glamorous heavy-lifting that led to those successes. I'm not suggesting any of those guys I just listed wouldn't still have top-notch careers without NJO, but playing at Harling's was one of the bricks that laid the foundation. I think they would all agree with that.

As for me? Well, I learned how to play blues in Db at Harling's. I learned that Woodchuck Draft Cider is not an acceptable drink choice for a grown man at Harling's. I got cut so bad by Matt Chalk and Nick Rowland on rhythm changes at Harling's that I actually moved in with my parents for two months so I could practice more over the summer. I dealt with my first, and most severe, romantic heartbreak as an adult at Harling's. When I applied for my first college teaching job, most of the things on my CV were an indirect result of playing at Harling's.

Clint, my brother. Thank you.