So…yeah.

I don’t want this to devolve into another well-worn cranky diatribe against being positive or encouraging. Far from it. I think that the intent behind all of these messages is awesome, and constantly aspiring for greatness is a common thread amongst all of the really successful musicians I know. In my own musical development, I know that my best growth has happened when I had a specific and ambitious goal in mind.

But what I think gets left out of the equation too often are the intermediate steps – the short term, manageable, incremental goals that add up to accomplishing your dreams. It’s great to set a lofty goal, but there is some danger there. There have been a handful of times as a teacher where a well-meaning student has written or verbalized a manifesto about his or her goals, replete with bold statements about fantastic achievements over unreasonably short periods of time, as though merely positing the thought was worthy of admiration and respect. Usually they have nebulous descriptions of what they’re trying to accomplish (ie, “I want to master (blank)”, or “I want to be able to (blank) well enough to get a gig”). And these manifestos seem to almost always be followed pretty quickly by the sobering realization that it’s going to be more work than they realized, and that they can’t sustain the effort needed to do what they set out to do in the time frame they had specified, and then finally, abandoning the plan together.

The root of all of this is very healthy: a genuine desire to be better. But students would be better served picking one large “long term” goal, and then identifying a series of corresponding “short term” or “medium-term” goals - some benchmarks to reach that lead up to checking off the final box. Identifying these benchmarks can create a satisfying sense of accomplishment that can quench that thirst for tangible improvement and keep you on pace towards a broader task. There’s nothing wrong with dreaming big, but being aspirational in and of itself won’t cut it. Here are some easy concrete, short- or medium- term goals that can motivate your practice.

Book a Public Performance With a Firm Date

Schedule a recital or a gig, with specific repertoire that will address the musical concepts you want to refine. Be careful not to schedule it so soon that you don’t have the time to comfortably develop your new skills – give yourself enough space to make sure you can pull it off. Conversely, don’t give yourself the option of cancelling if you feel the pressure a few weeks ahead of the performance. Want to get better at playing modal jazz? Work up two sets of Wayne Shorter compositions and bill it as such on the event flyers. Classical saxophone articulation? Program a recital including some baroque transcriptions. A word of caution, though: if you’re programming primarily or solely to address deficiencies, this might be better saved for a non-degree recital.

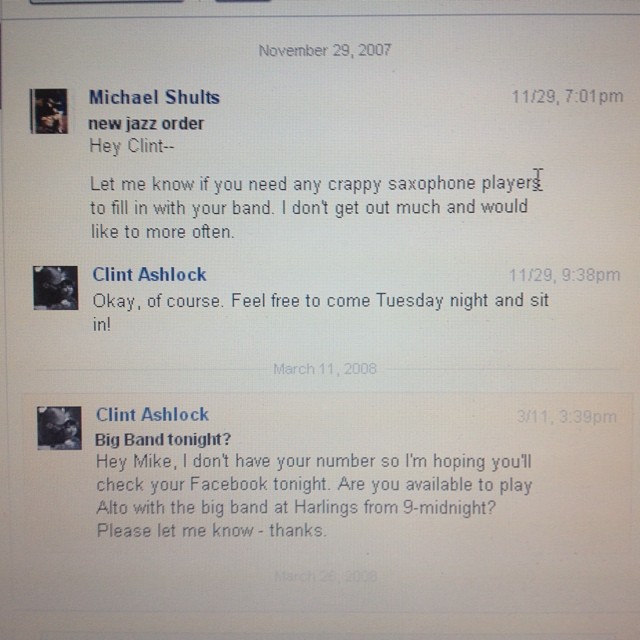

Last month I had the distinct pleasure of hanging with my friend and All-Universe First Team Saxophonist Nathan Bogert and working with his saxophone studio and the jazz ensembles at Ball State University. Dr. Bogert and I have become close since meeting two and a half years ago when he gave a guest recital at UMKC while I was working on my doctorate there. While having dinner in Muncie, Nate told me that he had scheduled that recital in Kansas City as a way to keep himself in shape, musically. He had finished his doctoral work at University of Iowa and had found another non-music related job that he enjoyed. “I could feel myself getting more invested in the job and getting too comfortable musically, so I booked that recital at a place where I knew I couldn’t cancel and I would have to be sharp”, he said (I’m paraphrasing). Of course, Nate has very high artistic standards and whatever he would perceive as “getting too comfortable” is probably better than anything most of us could ever dream of – but I digress. It was illuminating to me to hear someone as accomplished as Nate talk about voluntarily seeking out a playing opportunity solely to push himself artistically.