How to Ask A Good Question in a Lesson or Masterclass

It seems like every time I go to a masterclass with a great musician, there is someone in the room that raises his or her hand during the question-and-answer session at the end and asks a question that seems very obviously designed for a specific purpose. And that specific purpose is to impress the clinician or the fellow attendees with what a great question it was; the actual answer is really only an ancillary benefit to having actually posited the query. I'm aware of this phenomenon partially because I know that I was guilty of it in my early music school days. Asking a question was a good way to make obvious my diehard fandom by casually dropping in something like "On your 1994 Criss Cross release, I noticed you..." or to indicate to my fellow music school colleagues how thoughtful I was about my practicing: "I've been working lately on leaving more space in my solos, and..."

A cousin of this technique is asking a question with the hope that the answer will immediately solve a problem. I find this to be pretty common in my own private teaching with both high school and college students, and again - I know that I was guilty of this as a student, too, so I don't mean to throw shade (to all of my current students reading this: you're all pretty much awesome and I love you). I get things like "I can't play this interval - do you have any tips?" or "How do you play this 16th note passage up to tempo?" And, of course - in some cases I can make a quick diagnosis, or more likely give them a suggestion for a different way of practicing that might shore up the problem. Maybe the student's thumb isn't resting on the octave key efficiently, or maybe there is an alternate fingering that can facilitate speed, but more often than not, the student has already been exposed to the right method for addressing the issue, and the answer is just...to practice more.

Here are a few ideas - feel free to use. Downloadable Dropbox link above.

A watershed moment in my development as a musician came when I realized that, while there are occasional "aha" moments from a teacher that lead to growth, it's far more likely that breakthroughs and important discoveries will happen on my own, as a result of persistent practice and experimentation.

One of the most important influences on my playing and teaching has been Steve Davis , director of bands at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Conservatory of Music and Dance. I am not sure that the phrase originates from Professor Davis - he may very well have borrowed it from one of his teachers or someone else - but he was always fond of saying:

“Never accept ‘no’ from an inanimate object.”

Photo cred: conservatory.umkc.edu

I remember one time folding on a particularly difficult excerpt in Wind Symphony rehearsal. I can't remember exactly what piece it was, but I'm thinking it was something by Chen Yi . As I packed up afterwards and left the rehearsal space, Professor Davis saw me with a frustrated scowl on my face and asked me what was up. "I can't play that. It's impossible," I said, about a passage that was not at all impossible. "Impossible?" he said with one eyebrow raised. "Did you practice it one thousand million times?" No, I said. "Well, go practice it one thousand million times."

OK, so maybe the advice wasn't that profound... but then again it kind of was, though, wasn't it?

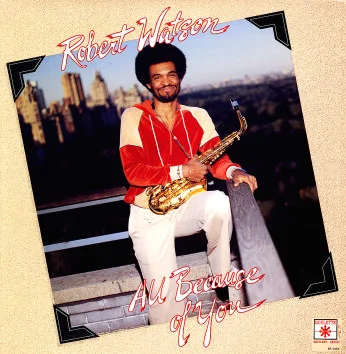

While studying with Bobby Watson as an undergraduate, I remember occasionally being frustrated when I would ask him a question that I thought deserved a straight-forward response, and not getting one. "Hey Bobby, what do you play over minor ii-V's?" I was hoping for "Well, Michael, here are the scale choices, and if you play these scales, you'll sound good." Instead, the "answer" was almost always "Have you checked out such-and-such a recording of so-and-so?" What Bobby was doing was encouraging me to seek out the answers for myself. He gave me a little nudge in the right direction, but I had to put in the time. It sticks better that way.

Did I share that anecdote mostly as an excuse to share this vintage album cover? Maybe. Maybe.

Good teachers will give you a method to practice and address weaknesses. They'll often give you a diagnosis and then a plan to fix your problems that might take weeks or months or years, and you have to trust that what they're telling you is going to work, because you might not see the results until you've devoted hundreds of hours to that particular course. But the key is always that you put the time in. Teachers can give you the method they used to develop a certain skill, but sometimes that method might not be exactly perfect you - what works best for you might be a subtle derivation of their plan, sort of like adding an extra spice or two to that recipe you got off of Pinterest (uh, I mean, not that i use Pinterest or anything, haha, ok I love Pinterest that's ok right?). But arriving at that method only happens through personal exploration and curiosity. The answer is almost never going to pay immediate dividends - and the sooner you stop expecting that, the better off you'll be.

If I take stock of my own strengths and weaknesses as a musician, it's really pretty simple: the things I do really well I do really well because I pushed myself and put the time in. The things I don't do well are because I haven't. I can't practically double-tongue because I haven't locked myself in the shed long enough for it to happen. I know how to double-tongue; there's no magic trick that someone's going to tell me that unlocks the secret for me. Just gotta get in there and work it out. I get locked up improvising in odd meters. I know how to shed that. I just gotta get on it. There are no easy answers - I just gotta practice.

So, my advice, that you didn't ask for, that I'm giving anyway because this is my stinking blog and you're reading it: if you've got a question to ask in a clinic or a lesson, start it with "How do you practice..." You're more likely to get something usable that way. Don't expect easy answers, and if something's not coming easy, know that the panacea is almost always... practice.